Background

The detached project supported by Erasmus+ via Leargas addresses the socio-economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people in Europe, focusing on those most socially excluded. A consequence of lockdown is an increase in the number of young people disconnected from employment, education and training supports. Lockdown has caused a suspension of youth services. Young people who were previously facing challenges are likely to have experienced a complete disconnect from services and supports, they will now need new supports to help them transition back into services. Young people who were previously socially excluded are now experiencing more extreme forms of social exclusion and alienation, leaving them vulnerable to radicalisation. The aim of detached work is to create connections for socially excluded young people with the services and supports they require.

Executive summary

Young people across Europe are currently sharing in a uniquely universal experience – lockdown. Those young people who were vulnerable and at risk of disconnecting from society and support, are now more vulnerable and further disconnected than before. The detached project focuses on the social and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people in Europe, building on a significant programme of work. Because of lockdown, the number of young people disconnected from employment, education and training supports will likely increase. Those already facing challenges will be in a worsening position and experience a complete disconnect from any services or supports, increasing the number of “Inactive NEETs” (not in employment, education or training). These young people are at risk of long-term social exclusion and poverty.

The respondents in this research were from 33 different organisations across 5 countries – Ireland, Sweden, Finland, Austria and Belgium. The most prevalent theme which emerged was isolation/alienation. The pandemic has changed the ways many of the respondents would engage their target groups and brought new challenges such as the adaptation to and eventual ineffectiveness of digital youth work. Although there was an increased demand for services the digital poverty often meant participation was low and after time ‘zoom fatigue’ also impacted upon engagement.

Respondents found the best practices to be being constantly visible to young people, providing packs to homes, engaging in digital youth work, socially distanced street work and competitions or sports. Other answers included interagency work, research and knowledge of the area, working in pairs and working from a bike. Respondents indicated they will adapt detached work in the following ways going forward, continued focus on street work and detached delivery, digital youth work, and continuing to evolve and adapt. Increased focus on mental health, social work and support for basic security and increased focus on advocating for NEETs and employment supports. The crucial element is being present, visible and available through detached outreach.

The research draws upon Eurofound’s (2016) Exploring the diversity of NEETS. Which found that today’s young people’s transition into adulthood is more complex and prolonged than previously, with more individualised and varied paths. NEETs have a wide variety of needs, this group is made up of a mix of young people who are not accumulating human capital through formal channels, whether voluntarily or involuntarily. We also know from Eurofound’s research that the solution for supporting disconnected young people is undeniably, outreach. Here is where the skills and energy of detached youth work come to the fore.

Detached work is a viable practical method considering current restrictions, thus practical considerations such as providing youth workers with sufficient PPE will remain important. As regards best practice, increasingly innovative methods are needed. This requires additional supports and professional development opportunities to empower street teams and detached youth workers to use their creativity, experiment and explore new ways of reaching young people. Youth workers need to know that their outreach is of great value. Digital youth work should continue to be used in tandem with street outreach once lockdown restrictions are eased. The varying circumstances of young people may mean some may be left behind in the rush to move back to physical spaces. Methods should reflect the diversity of the main target group. The core for policymakers is that the main target group, NEETs, already existed and this pandemic is exacerbating their situation. This group is diverse, and a one-size-fits-all solution will not be enough. The diversity of the issues facing NEETs should not be a deterrent from addressing their needs.

Findings

The detached project addresses the social economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people in Europe, focusing on those at risk of social exclusion or already socially excluded. A consequence of lockdown is that the number of young people disconnected from employment, education and training supports will increase. For young people who previously faced challenges, their situation will have been exacerbated and they are likely to be experiencing a complete disconnect from any services or supports. Our greatest concern is for those young people, not in education or training, who are known to be inactive in relation to supports – “Inactive NEETs” (not in employment, education or training). The situation of these young people is worsened since many of them do not benefit from supports because they are “invisible” to service providers. The detached project builds on a significant programme of work and is likely one of the most relevant interventions for socially excluded young people at this time.

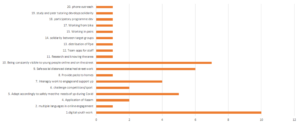

The respondents in this research were from 33 different organisations across Ireland, Sweden, Finland, Austria and Belgium. This research elicited a volume and diversity of answers from a relatively small number of respondents, however, when considered in the specific context of our work the diverse answers describe several themes that are relevant to supporting vulnerable young people:

|

|

Eurofound’s (2016) Exploring the diversity of NEETS, shows that shifts in attitudes, perceptions and behaviours in European societies and an augmented labour market have resulted in today’s young people’s transition into adulthood becoming more complex and prolonged than in the past. Their paths are individualised and show a great deal of variety. The traditional approaches used to try to understand the factors that affect young people’s transition to adulthood are becoming less relevant. An important element to consider in this is that the historic depictions of employment and unemployment may not fully capture all situations or positions that impede the opportunities to acquire human capital – the economic value of a worker’s experience, skills and personal attributes. NEETs emerged during the 2008-2013 recession, the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to create new challenges for this already vulnerable group.

Young people who are vulnerable are so as a result of multiple causal factors. Our current context of the pandemic lockdown has brought a universal experience to young people across Europe. Part of this universal experience is that those young people who were vulnerable and at risk of disconnecting from society and supports are now more vulnerable and further disconnected than before. We also know from Eurofound’s research that the solution for supporting disconnected young people is undeniably, outreach. Here is where the skills and energy of detached youth work come to the fore.

The need for this programme is due to the worsening situation of a significant minority of young people who experience social exclusion, known to have been most affected by the negative consequences of lockdown, which has exacerbated their pre-existing disadvantage (ESRI, 2020). The combination of these circumstances puts these young people at risk of long-term social exclusion and poverty. Lack of data sharing and effective outreach are the two main reasons for this invisibility.

The young people who do not attend, engage or take up opportunities for supports are at the highest risk. Precisely defining, finding and supporting these young people is the burden of this programme. The main target groups named by respondents were socio-economically disadvantaged young people, NEETs, young women/girls, young migrants and refugees, Roma and traveller young people, young people who are at risk of involvement, or already involved, in the criminal justice system, young people in care homes, young people who are known to be radicalised or at risk of radicalisation and young people involved in substance/drug abuse. For young people who may fit into two or more of these groups their opportunities to engage with supports is further decreased.

Though a range of different answers were received, respondents mainly engaged young people, on the streets, at public meeting places, in their own homes, through the internet and digital spaces. Respondents were based in a variety of rural and urban settings. The pandemic had changed the ways many of the respondents would engage their target groups and brought new challenges. The new challenges that emerged for youth workers in reaching out to their target group included the adaptation to and eventual ineffectiveness of digital youth work. Many services were run completely online, although there was now increased demand for services the digital divide often meant participation was low and following extended lockdown restrictions ‘zoom fatigue’ began to also impact upon engagement.

Respondents found the best practices to be being constantly visible to young people, providing packs to homes, engaging in digital youth work, socially distanced street work and competitions or sports. Other answers included interagency work, research and knowledge of the area, working in pairs and working from a bike.

Respondents indicated they will adapt detached work in the following ways going forward:

- Continued focus on street work and detached delivery

- Continue to evolve and adapt

- Continued digital youth work

- Increased focus on mental health

- Increased social work and support for basic security

- Increased focus on advocating for NEETs and employment supports

- Being present, visible and available through detached

Detached work will come to the fore as a practical method considering current restrictions. The youth work sector needs to focus on young people being reached through detached work and become increasingly innovative in their methods. To facilitate this, it may involve increased supports to empower street teams and detached youth workers to use their creativity, experiment and explore new ways of reaching young people.

Digital youth work can, and should, continue to be used. Consideration will need to be given to the varying circumstances of young people, especially those who may be left behind in the rush to move back to physical spaces. The diversity of need should be reflected by a diversity in methods. Professional development opportunities should be provided in the areas of mental health, digital media, career guidance, employability coaching. It will also remain important that youth workers are provided with sufficient PPE.

Together with education, community and other sectors, youth work can play a role in preventing radicalisation in its early stages. To make the most meaningful contribution to the prevention efforts, the youth work sector should focus on its strengths and advantages, such as youth empowerment, participation, learning and inclusion. Youth workers should seek to better understand the phenomena of violent radicalisation and engage in continuous learning and reflection on the challenge and how to tackle it. The practical challenges regarding the implementation of preventive activities and the need for improving the impact of current practices are inspiration for further work. (Garcia López & Pašić, 2018) Further recognition and support of the role of youth work from member states and the European Union is needed. The value of youth work lies in its flexibility in addressing the realities of young people. Youth work can make the difference in tackling radicalisation by supporting young people, especially those at risk of alienation and social exclusion, and empowering them to deal with the challenges of growing up in a complex, pluralistic modern society. (Results of the expert group set up under the European Union Work Plan for Youth for 2016-18)

This research highlights the need to focus on young people who are most socially excluded and least likely to transition successfully from lockdown. Exclusion and alienation can lead to concerning social issues such as radicalisation. Youth radicalisation and the associated use of violence has been a growing concern in Europe. There has been a considerable increase in hate speech, hate crimes and attacks on migrants and refugees, and violent xenophobia, as well as a rise in religious and political extremism. These concerns have highlighted the urgent need to work with young people, in order to identify and address the root causes and prevent violent radicalisation. (García López & Pašić, 2018)

This can be expected to rise with the recession that COVID-19 has already triggered, leading to further reduction in education and employment opportunities. Also, in the context of the COVID-19 crisis we are seeing a rapid growth in less usual types of radicalisation and the emergence of new types of extremist ideas and networks based on conspiracy theories and fake news, much of which is and will be exploited by radical recruiting groups, some traditional and some newer.

References

ESRI, (2017) Off to a Good Start? Primary School Experiences and the Transition to Second-Level Education Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin.

ESRI, (2020), The implications of the Covid 19 Pandemic for Policy in Relation to Children and Young People: A research Review, Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin.

Eurofound (2012), NEETs – Young people not in employment, education or training: Characteristics, costs and policy responses in Europe, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Eurofound (2014), Mapping youth transitions in Europe, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Eurofound (2016), Exploring the diversity of NEETs, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Freeman, R. and Wise, D. (1982) The youth labour market problem: Its nature, causes, and consequences, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

García López, M. A. & Pašić, L. (2018) ‘YOUTH WORK AGAINST VIOLENT RADICALISATION Theory, concepts and primary prevention in practice’ The Youth Partnership Report, Council of Europe and European Commission

Nalbantian, R. H., Guzzo, R. A., Kieffer, D. & Doherty, J. (2004) Play to Your Strengths: Managing Your Internal Labor Markets for Lasting Comparative Advantage. New York: McGraw-Hill

OECD (2016), Faces of Joblessness in Ireland, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/Faces-ofJoblessness-in-Ireland.pdf

Williamson, H. (1997), ‘Status Zer0 youth and the “underclass”: Some considerations’, in MacDonald, R. (ed.), Youth, the ‘underclass’ and social exclusion, Routledge, London.

Results of the expert group set up under the European Union Work Plan for Youth for 2016-2018 (2017) ‘The contribution of youth work to preventing marginalisation and violent radicalisation – A practical toolbox for youth workers & Recommendations for policy makers’ Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union